The Day My Spine Shattered—and the Surgeon Who Rebuilt It

A Spine Surgery Survivor’s Journey Through Trauma, Trust, and the Science of Hope

You don’t think about your spine—until it’s the only thing you can think about.

That moment came for me in the wreckage of a car crash that shattered more than just bone. One minute, I was driving. The next, I was broken—inside and out. I had sustained an unstable lumbar fracture, the kind of injury that changes everything. My spine—the structural core of my body—was compromised. I couldn’t sit up. I couldn’t walk. I didn’t know if I ever would again.

Enter Dr. Wylie Lopez, MD, an orthopedic spine surgeon who specializes in moments like this. To him, this wasn’t just surgery. It was stabilization. Preservation. The opportunity to reclaim what had been violently taken from me.

And he did it—within 24 hours.

Holding a Life in His Hands

Image Credit: Dr. Wylie Lopez

When I asked Dr. Lopez what it feels like to literally hold someone’s ability to walk—or even live—in his hands, he didn’t romanticize it.

“It’s one of the most stressful parts of what I do,” he said. “There’s a lot of uncertainty in medicine, especially with trauma. Even a technically perfect job can have an uncertain recovery. These are the situations that keep us up at night.”

But that pressure, he explained, is exactly why mastery matters.

“I focus on the things I can control—my technique, my decision-making, my hands.”

Those hands saved my life.

Breaking the Myths Around Spine Surgery

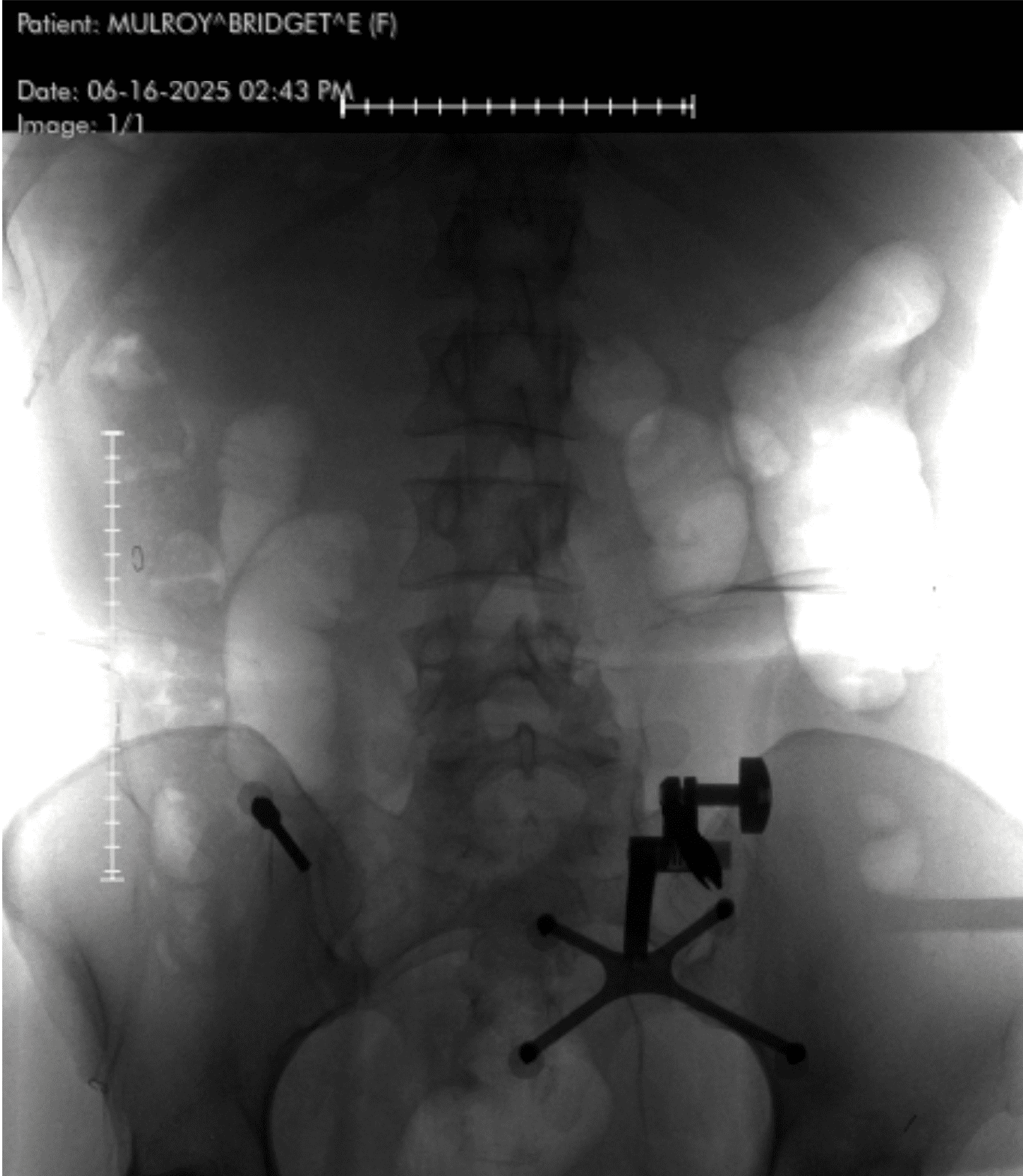

Image Credit: Bridget Mulroy

Before my surgery, I was terrified. I had heard all the horror stories—paralysis, chronic pain, botched fusions, addiction to pain meds. But Dr. Lopez sees those narratives as outdated and oversimplified.

“Spine surgery has reached a technological revolution,” he said. “We now have robotics, augmented reality, and minimally invasive techniques that make even complex surgeries safer and outcomes better.”

One of the biggest myths? That physical therapy doesn’t work and that surgery is inevitable.

“About 80% of my patients get better with PT, exercise, weight loss, and managing depression,” he explained. “I operate on the other 20%. Surgery is often the last line of defense.”

But in trauma cases like mine, that calculus changes quickly.

The Science of Emergency Stabilization

“When I realized your fracture was unstable,” Dr. Lopez told me, “I knew you wouldn’t be able to mobilize without internal stabilization. Letting you try to walk could’ve worsened the fracture, caused spinal deformity, or led to nerve damage and chronic pain.”

Instead of using an external brace, Dr. Lopez used hardware—screws and rods—to create internal support.

“Technically, you didn’t have a spinal fusion,” he clarified. “You had spinal instrumentation and stabilization. A fusion requires bone grafts and biologic processes to encourage new bone growth.”

What he gave me, though, was just as powerful: a structurally sound spine—and a second chance at mobility.

Inside the Operating Room

When Dr. Lopez described the actual procedure, I was floored by the precision involved.

He performed a minimally invasive posterior lumbar instrumentation from L2 to L5. That means he made small incisions guided by real-time navigation using a machine called the O-arm—a rotating intraoperative CT scanner. A localizing pin in my pelvis communicated with a computer, which told him exactly where to place each screw.

“Once the screws are inserted,” he explained, “I use an X-ray to place the rods. The key decisions involve knowing which levels to include, ensuring screw trajectory is perfect, and having a plan if something doesn’t go right.”

I asked: What happens if something doesn’t go right?

“If a screw is placed too far forward, it could hit major blood vessels. That could lead to death or severe disability.”

He didn’t say this to scare me—he said it because that’s the level of consequence spine surgeons face every time they step into the OR.

Minimally Invasive, Maximally Transformative

So what does “minimally invasive” actually mean?

“It means reducing collateral damage,” Dr. Lopez said. “We avoid dissecting the large muscles of the spine. That means less blood loss, less post-op pain, and faster recovery. The same applies to endoscopic and lateral-based approaches.”

Within 24 hours of surgery, I was standing. Walking. Slowly, yes—but it felt miraculous.

“That’s because the spine was no longer unstable,” he said. “Once you fix the problem mechanically, movement becomes tolerable again. And the body is incredibly resilient.”

The Mental Game of Recovery

Of course, recovery isn’t just physical—it’s emotional.

“The mental part is half the battle,” Dr. Lopez told me. “People with depression have worse outcomes, even with the same surgery. I encourage positivity and resilience because it truly impacts healing.”

In my case, he said my recovery was above average. Why?

“You’re young, healthy, and motivated. You also have a strong pain tolerance, which made physical therapy more manageable.”

He also emphasized how crucial pre-injury fitness and mental health are in predicting outcomes.

“Most of my patients return to a normal life, as long as they follow restrictions and manage risk factors like smoking or uncontrolled diabetes.”

Pain, Opioids, and the Balance of Trust

Pain management is one of the most delicate parts of spine surgery recovery. The pain is real—but so is the fear of opioid dependency.

“There needs to be a solid post-op pain plan,” he said. “Clear boundaries, expectations, and sometimes a narcotics agreement. But we also leave room for compassion. If someone is suffering, we work with them.”

A Future Built on Titanium—and Hope

Image Credit: Bridget Mulroy

I asked him what becomes of all the hardware—the screws, rods, and implants—once the spine heals.

“They support the body through the healing process,” he said. “Once bone growth stabilizes the segment, it’s like the hardware isn’t even there. But if a surgery doesn’t heal properly, the hardware can become loose, break, or even get infected.”

And what about those rumors of becoming a “human barometer”?

“We hear that a lot,” he laughed. “There’s no definitive proof, but barometric pressure may affect tissues post-op. The jury’s still out.”

If You’re Afraid…

To anyone frozen by the fear of spine surgery—especially those suffering in silence from chronic pain—Dr. Lopez had this to say:

“I try not to push. My job is to educate. If they ask what I’d do, I imagine they’re my own parent and answer with that in mind.”

That’s what makes him special. Not just his surgical skill—but his humanity. He’s not just cutting bone—he’s restoring lives.

My Life After Surgery

Today, I live without fear of collapse. Without the dull, grinding ache that once defined my every movement. I walk. I travel. I live. And I owe that to the science of modern spinal medicine—and to Dr. Wylie Lopez, whose steady hands held my future.

He says he remembers every patient he’s treated with spinal cord injury and paralysis. He carries them with him.

I carry him with me, too—not just in the screws and rods that stabilized my spine, but in the faith I now have in my body, my healing, and what’s possible when medicine meets miracle.

If you’ve been told your back is broken—or that your pain has no solution—know this:

There are people like Dr. Lopez who dedicate their lives to rebuilding what feels shattered beyond repair.

There’s hope. There’s healing.

And yes, there’s life on the other side of broken.

Interview

1. Your hands gave me back the ability to walk. What does it feel like, as a spine surgeon, to quite literally hold someone’s future mobility—and sometimes their life—in your hands?

“It’s certainly one of the most stressful parts of what I do. There is a lot of uncertainty in Medicine and part of my job is to master all the things that are in my direct control–things I can be certain about, such as surgical technique and indicating the appropriate surgery for someone. In certain instances, such as a severe trauma with paralysis, even a technically perfect job can still be clouded by an uncertain recovery. These are the most stressful situations and the ones that keep us up at night.”

2. What led you to specialize in spine surgery? Was there a defining moment or personal experience that drew you to this field of medicine?

“It happened very organically. In my training, I had the pleasure of working with some world-renowned surgeons. We spent many hours together operating and seeing patients in the office. A general interest in the subject matter and the realization that I was becoming quite good at it is what led me to pursue more time in the operating room with these surgeons. Once I really got to know these spine surgeons, I realized that I had a lot in common with them and began pursuing more opportunities to work with them. That led to more cases, a stronger knowledge base, and better hands. And thus, a spine surgeon was born.”

3. Spine surgery carries an almost mythical level of fear for many—images of paralysis, prolonged recovery, or permanent disability. What are some of the biggest misconceptions you’ve encountered, and how does modern spinal medicine challenge those fears?

“Misconceptions certainly run wild in this field. Physical therapy not working is probably one of the biggest ones. I find that physical therapy typically fixes about 80% of my patients and I end up operating on the other 20%. It’s actually astounding how many people find relief just from exercise, weight loss, and optimization of co-morbidities and mental health (depression plays a big role in recovery). Another big one is people just assuming that they are going to do poorly after spine surgery because everyone has a friend with a horror story. In today’s world, spine surgery has reached a technological revolution marked by robotics, augmented reality assisted, and minimally invasive surgery which has transformed the field for the better. These enabling technologies have made even the most difficult surgeries more routine and have helped improve patient outcomes. This is better for everyone involved.”

4. You operated on me within 24 hours after I was told my spine was broken. From a clinical standpoint, what’s happening in the body when a spinal fracture like that occurs—and why is timely intervention so critical?

“There is a lot that goes on after the body sustains a fracture. The most important from the perspective of a spine surgeon is how it ultimately affects your mobility, spine stability, and nerve integrity. If a person lays in bed immobile, they have a much higher risk of developing blood clots or pneumonia, which can be life threatening. This is why getting people up and moving is such an important goal for surgeons. When I realized that your fracture was unstable, I knew that you would not be able to mobilize until your fracture was stabilized. If I let you walk with an unstable spine fracture, you could have developed worsening position of the fracture, a spinal deformity leading to chronic pain and possibly requiring an even bigger/more morbid procedure, and even nerve injury from bony compression leading to extremity deficits, disability, and chronic nerve pain.”

5. Many believe spinal surgery should only be used as a last resort. But it saved my life. In what scenarios is spinal fusion actually the safest and most effective first-line treatment?

“There is some nuance here with the terminology. You underwent a spinal instrumentation and stabilization without a fusion. I used hardware to essentially “brace” your spine from the inside (as opposed to an external brace which would not have worked in this case). A spinal fusion requires biologic assistance from the body in addition to stabilization of the segment. That would mean using bone graft and carpentry work to the bone that would facilitate signaling pathways that calls bone cells to the area to form more bone. Spinal fusions are typically required in instances where we are removing bone and know that we are going to de-stabilize a segment in the process, when we are attempting to change the shape of the spine and want it to heal in that new position, or when there is a severe pathology that needs new bone to form to fully stabilize the segment in the long term.”

6. Can you walk us through the steps of a posterior lumbar spinal instrumentation, like the one I had—from incision to closure? What kinds of real-time decisions do you have to make in the OR when unexpected complexities arise?

“The process behind a posterior instrumentation with stabilization is as follows (I did this minimally invasive so it’s slightly different): I placed a metal localizing pin into your pelvis which talks to the computer in the room which helps us with real time screw navigation. We spin a large machine called an O-arm which performs in intraoperative CT scan which gives us a lot of information about your bones. We use that as a real time navigation for placing the screws into the bones. We then used a special marker to know exactly where to place your incisions based on the real-time feedback from the navigation (we can keep the multiple incisions small because of this technology). Once the incisions are made, we dissect down the skin, fascia, muscle, and down to the bones of the spine. From there I use the real-time navigation to understand the trajectory of the screw and place each one with a set of instruments—first an awl to make a small hole in the bone, then a tap to widen that hole a bit in order to better facilitate screw insertion, then the actual screws. Once the screws are inserted, I use an x-ray machine to help me place the rods. The real decision making here includes the pre-operative planning and knowing which levels to include, the proper screw trajectory and to know if the feedback from the live navigation is accurate, and what to do if a screw isn’t perfect.”

7. From a surgical perspective, what makes a multilevel spinal surgery (like mine from L2 to L5) especially complex or high-stakes?

“You need to make sure that the screws are placed properly or they could pull out or the fracture won’t heal. If the screws are accidentally placed a little too anteriorly (meaning too far forward), they can cross the front of the spine and hit one of the large blood vessels; this could lead to death or severe disability.”

8. We often hear the term “minimally invasive” in spinal care, but what does that actually mean in practice? How have surgical techniques evolved over the past decade to reduce trauma and improve recovery?

“”Minimally Invasive” or MIS, is a term used to describe a deviation from conventional spine surgery that seeks to minimize collateral damage to other structures and improve recovery. With MIS surgery, there is less dissection of the big muscles of the spine which means less damage to those muscles and a faster return to function, which for the body is one of the most important things. The same can be said about other nearby structures with other types of MIS surgery such as lateral-based indirect decompressions, tubular and endoscopic surgeries, etc.”

9. The trauma of a spinal injury isn’t just physical—it’s emotional. How do you consider the mental and emotional toll of surgery when working with patients? Do you see psychological resilience as part of the healing process?

“The mental part of this process is half the battle. I try to encourage patients to think positively and be resilient as it can contribute to their post-operative recovery (or lack thereof). Patients who are more motivated tend to work harder with post-op mobility and physical therapy and those with depression are shown to have [the] worst outcomes, even if the surgery is the same.”

10. For people who fear losing their independence after surgery, what can you share about modern recovery timelines and mobility outcomes? Is the idea of being “bedridden for months” outdated?

“Recovery is often highly dependent on the magnitude of the injury. We find that the patient’s pre-injury neurologic function and physical activity status plays a major role in their post-operative recovery. Being bedridden for a spine injury that does not have any neurological changes pre-operatively is quite rare nowadays. Of course, if you have a spinal cord injury then that picture can drastically change.”

11. Post-operative pain can be intense, but so is the fear of dependency on pain medication. How do you help patients walk the line between managing pain effectively and avoiding long-term reliance on opioids?

“There has to be a good post-operative pain plan that both patient and physician can agree on. A lot of physicians require a narcotics contract beforehand so that there is no confusion as to what the plan is. Of course, everyone’s pain is different and there is always wiggle room when you know a patient is suffering. I think setting clear boundaries goes a long way with this part of the patient-physician relationship.”

12. I was walking within 24 hours of major spinal surgery. What does that say about the body’s resilience—and how much of that outcome is made possible by surgical precision and planning?

“That part is entirely dependent on stabilization of the unstable fracture. Once that piece is no longer displacing with simple movements (after fixing with screws and rods), standing, shifting, moving, etc all becomes far less painful. The body must get used to the fact that it had surgery and it has plenty of resilience to overcome that hurdle.”

13. How do you determine when a patient truly needs surgery versus when they might benefit more from conservative treatment like physical therapy, injections, or pain management?

“It’s totally dependent on their initial presentation. With fractures and spinal cord injuries, it’s often based on a set of rules that we follow—it starts with determining stability and understanding if the patient has a neurologic injury or not. It is actually MORE difficult with the elective surgeries. It’s trying to understand the patient’s situation, how much better you think you can make them with an intervention, and how much they have tried initially. In situations where patients are in pain but it’s manageable, I almost always try to start them off with 6 weeks of physical therapy and some sort of prescription strength pain medication such as an anti-inflammatory. If that fails, depending on their MRI, we may try injections or alternative forms of treatment such as acupuncture, chiropractic care, muscle stimulation, massage therapy, etc. I consider myself to be a conservative surgeon and surgery is often the last line of defense.”

14. You’ve treated hundreds, maybe thousands, of patients over the years. Is there one case that stands out—something that changed how you approach your work or reminded you why you chose this profession?

“I wouldn’t say there is one particular that stands out; there are many that have stuck with me throughout the years. The most painful are young patients who have sustained spinal cord injuries with paralysis. When you take call at a level 1 trauma center, you will meet these patients at some point in your career. I remember each and every one of them.”

15. Let’s talk about the hardware—titanium rods, screws, cages. What role do they play long-term? Can patients feel them indefinitely, or does the body adapt?

“The whole point of the hardware is to assist the body in performing its natural process. Once the fusion has matured, the body will function as if the hardware isn’t even there. In some instances, when a surgery does not heal properly (pseudoarthrosis/nonunion), the hardware can loosen, break, or become chronically infected. In these cases, they can be irritating and sometimes have to be removed or replaced.”

16. Some patients say they become “human barometers” after spine surgery. Is there truth to weather sensitivity in relation to spine health, or is that more anecdotal?

“This is a tough one. There is so much anecdotal evidence but there is nothing that we can point to that definitively explains why it happens. There is some loose evidence that points to differences in the temperature and barometric pressure (atmospheric pressure) affecting post-surgical tissue differently. The reality is, we don’t know.”

17. Spine surgery today is drastically different than it was 20 years ago. What breakthroughs—whether in robotics, imaging, or technique—have most revolutionized the field?

“I think the biggest game changers are robotics and endoscopic techniques. Robotic assisted surgery has leveled the playing field and has made the more difficult techniques easier to do. Endoscopic surgery is a new form of ultra minimally invasive surgery that allows faster recovery times and quicker return to work with little to no narcotic use after surgery. Not all patients are candidates for this type of surgery. This is a technique that I am currently pursuing.”

18. There’s this fear that spinal surgery limits a person’s life forever. But you had me walking within days. What kinds of lives do your patients typically return to—athletes, parents, travelers? Is a full life after surgery still possible?

“There are different levels to spine surgery. Bigger surgeries can lead to bigger changes in a person’s life. It is also very much dependent on a patient’s pre-injury/pre-surgery functional level, nutritional status, age, and motivation. We know that comorbidities such as uncontrolled diabetes, obesity, and smoking can really complicate someone’s post-operative recovery and increase the risk of a complication. I would say that most patients return to a normal life as long as they follow the post-operative restrictions and minimize modifiable risk factors.”

19. At my follow-up, you told me I was progressing faster than average. In your experience, what contributes to an ideal recovery? How much of that is physical, and how much is mental?

“You are a young/healthy person with no medical problems and a good outlook on life. People like you typically do great! The biggest question mark for a surgery like yours is how people are going to tolerate post-operative pain. In your case, I would say you have a strong pain tolerance which made your post-operative physical therapy easier to tolerate.”

20. If you were sitting across from someone terrified of spine surgery—someone in chronic pain but frozen by fear—what would you say to them, doctor to human being?

“This is what I do every single day, and it is highly dependent on their pathology and situation. I try to never force them in a particular direction unless it is a dire circumstance. Instead, I believe that my job is to educate them about their options and if they ask me what I would do, I picture them as one of my parents before giving them an answer.”

The post The Day My Spine Shattered—and the Surgeon Who Rebuilt It appeared first on Social Lifestyle Magazine.

:quality(85):upscale()/2025/10/09/670/n/1922283/00b944c868e7cf4f7b79b3.95741067_.jpg)

:quality(85):upscale()/2023/09/18/918/n/1922398/a1136b676508baddc752f5.20098216_.jpg)

:quality(85):upscale()/2025/09/09/891/n/1922283/7222624268c08ccba1c9a3.01436482_.png)

:quality(85):upscale()/2023/10/03/668/n/1922283/1f15c8a9651c2d209e5eb5.32783075_.jpg)